Designing the Living Machine

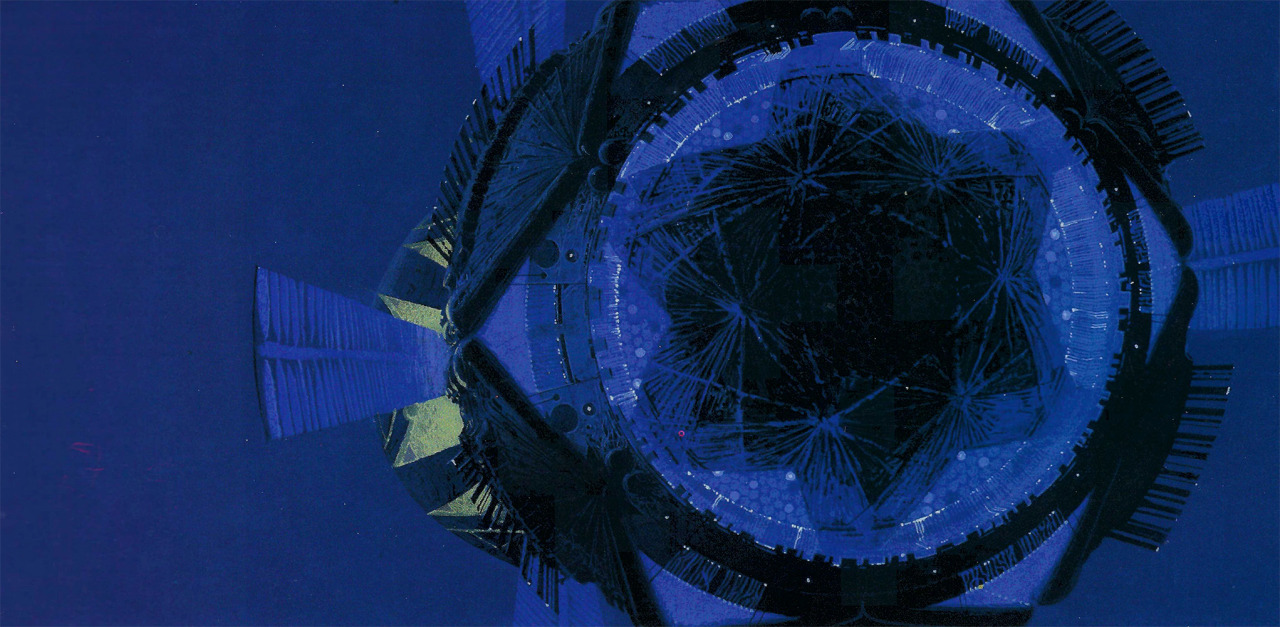

After the planned pilot of the second Star Trek television series, “In Thy Image,” became the basis for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Richard Taylor as art director assumed responsibility for designing the mysterious entity known as V’Ger (then still written as “Vejeur”). Mike Minor had drawn a few concepts for Phase II. Tony Smith, brought in by Taylor, developed the entity further.

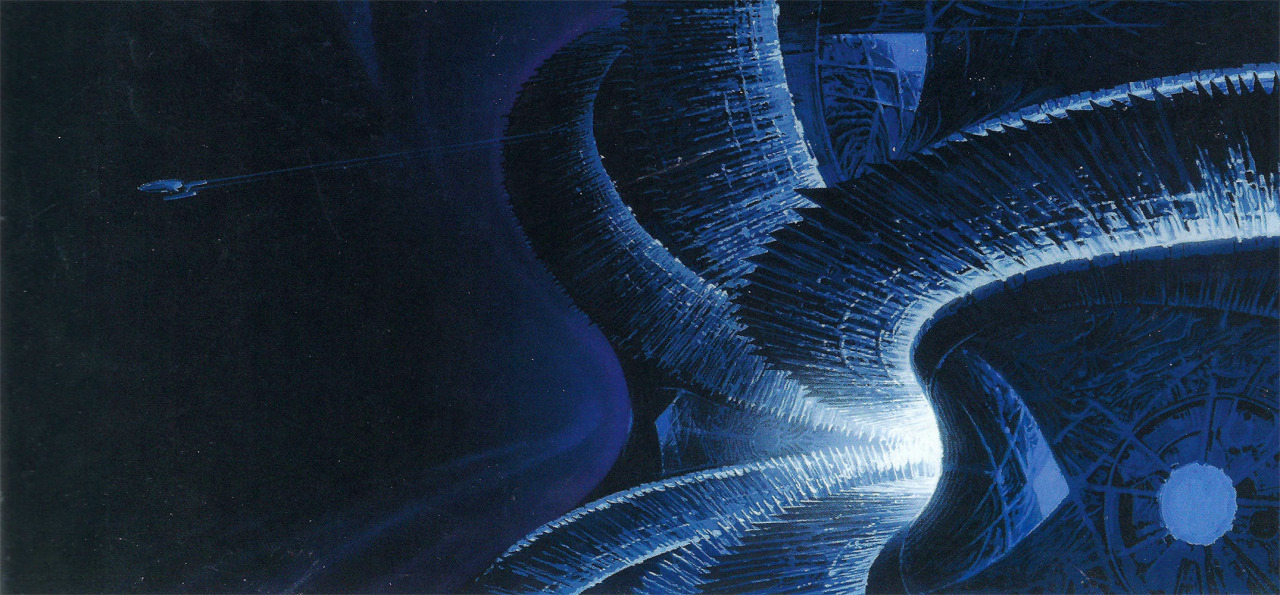

Taylor’s idea was that the whole of V’Ger would never be seen. “It was to be a dark object, not some light-covered mothership from Close Encounters,” he told Tracy Tobias in 2001. “It’s always more mysterious to show less and leave it to the imagination.”

There’s a part of V’Ger toward the tail section, where there is a huge sphere that rotates and in the center of that sphere is the old Voyager 6 probe. Our V’Ger design is much more complex and much more mysterious. For one thing, it would have been a lot more interactive with the Enterprise.

Taylor’s philosophy was to make V’Ger a living machine.

It would have “morphed” and on the inside the walls would have been iridescent and changed as the Enterprise moved past them.

Images of the Enterprise would be projected on the walls as V’Ger was analyzing the ship. Parts of walls would break apart like a flock of birds or a swarm of insects.

The swarms would go from one place to another and reassemble. You could think of the particles as digital energy or digital information. I wanted it to be a very metamorphical and very mysterious place.

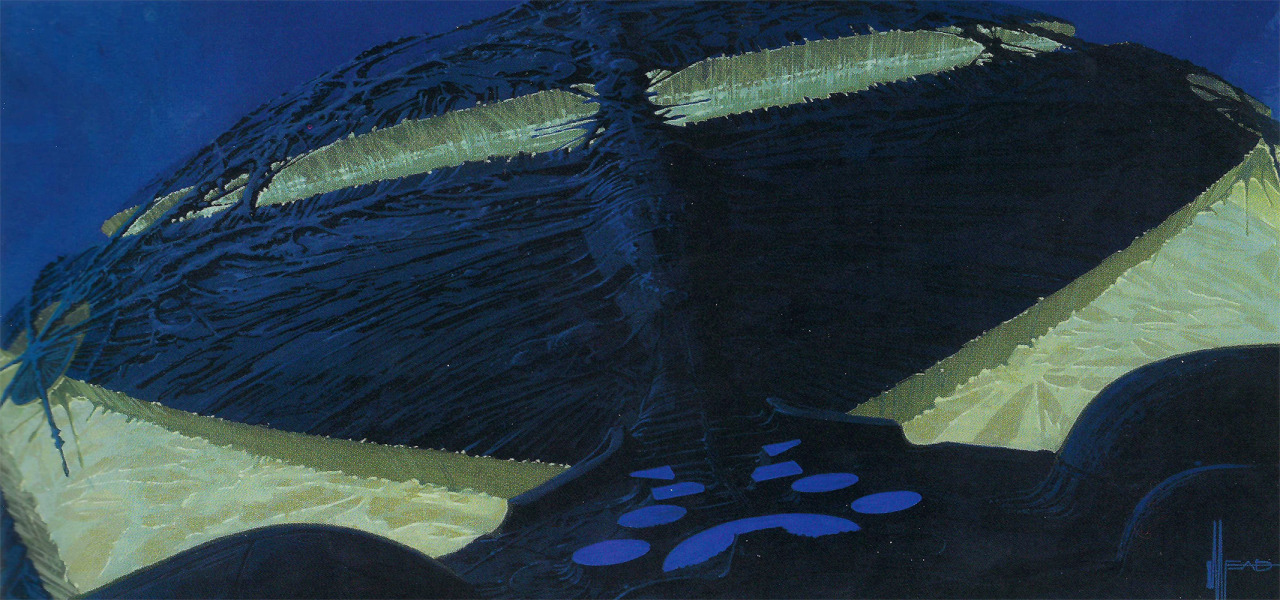

For the exterior of the thing, one of the design concepts I had was to photo-etch thin metal plates so that the outside surface would have multiple levels which would continually move, creating different patterns. We found a material that you could apply like paint that when heated with warm air from a blower would change color. It had an iridescent color quality that I was looking for, like a beetles’ back or butterflies wings. I wanted V’Ger’s skin or surface to change color near the Enterprise as it moved over the surface. I wanted the image of the Enterprise to be left like glowing phosphor images along the walls of V’Ger.

Transformation

At the end of the film, V’Ger would have evolved into a higher being. “What we had storyboarded was that the whole V’Ger craft unfolds and turns into this incredible object in space,” said Taylor.

That effect would have started where Kirk, Spock, McCoy and the Voyager 6 was and would have radiated outward from there through the ship. There would have been this change that goes through V’Ger’s interior and then to the outside, unfolding into a big flower kind of thing with all these radiating colors and such.

The visual effects in 2001 Director’s Edition approximated this vision, but the original 1979 film looked less impressive.

Weird fish

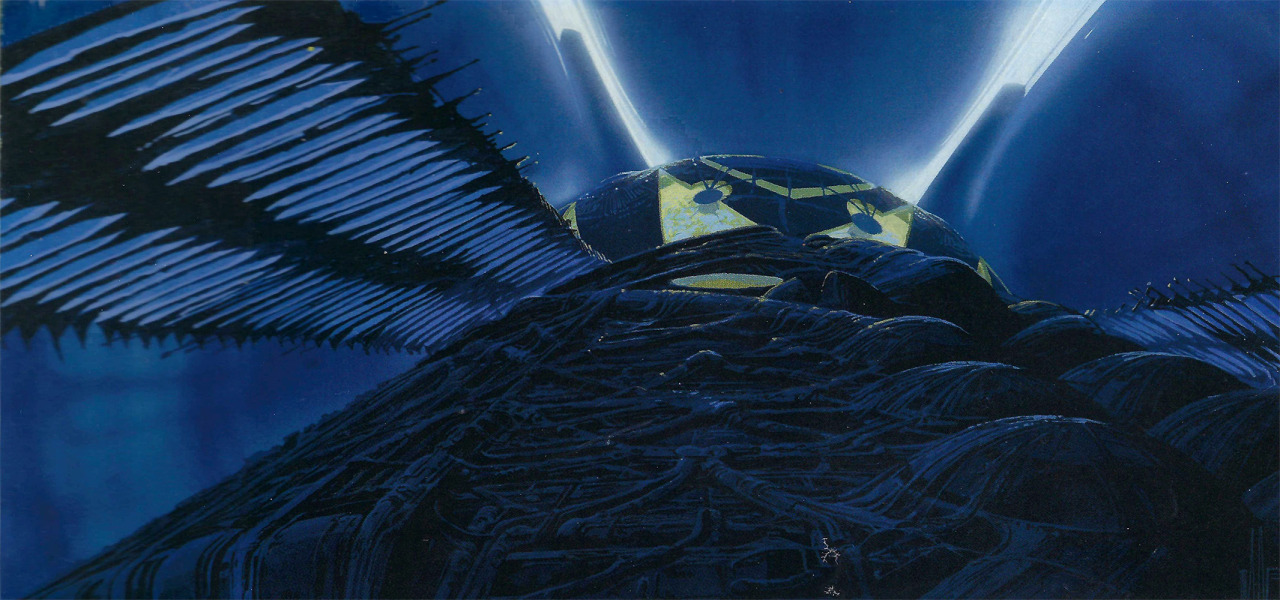

Brick Price, whose company Brick Price Movie Miniatures was brought in by Robert April on The Motion Picture, worked on the V’Ger model, or at least the early stages of it while Taylor was art director.

The model they started on in August 1978 looked like a cigar with a maw that opened up. They disliked the design, feeling it was too reminiscent of “The Doomsday Machine”, and there was already enough trouble with the script being similar to that episode and “The Changeling”.

But we did a lot of tests working with the textures like paint, color and light, things of that sort, and it wound up with a very organic Art Deco look to it.

Taylor was an avid deco fan. That one might have been interesting had they gone with it. It would have had a bubble on it and the Voyager craft would have been on an island underneath one of those. The whole skin surface was sort of iridescent. But then Paramount decided to have miles and miles of white and not let people know what it looked like exactly. Ours was really bizarre and all convoluted with things hanging off it. So every time it changed hands it changed completely. Taylor’s original interior concept of V’Ger was extremely complex. You can see all sorts of actual light functions and all sorts of spheres representing the V’Ger concept of life.

Taylor felt the changing of hands compromised the design. “We had built test pieces and had done extensive tests of processes we were going to use when we finally began construction,” he said. But Douglas Trumbull, the movie’s director of “special photographic effects” (as VFX were called back then) was unimpressed. “I was told Trumbull described the exterior as a ‘weird fish’.”

A new approach

Trumbull was brought in by the studio with less than a year to finish the effects. He told The Hollywood Reporter in 2014 that Robert Abel and Associates — the company Taylor worked for — had made some fundamental mistakes by using technology that wasn’t ready for primetime. They also had no motion-picture experience. A desperate Paramount gave Trumbull carte blanche.

He divided the work between two teams: his would work on the interior while John Dykstra was put in charge of V’Ger’s exterior.

The work that the Abel studios had done was abandoned, and the teams set out to develop entirely new concepts. Famed illustrators Robert T. McCall and Syd Mead were hired to design a new version of the giant spacecraft, with Mead’s concepts having the biggest influence.

The model of V’Ger they built was never seen in its entirety, but it was an incredible beast, 60 feet long. Dykstra remembered that constructing it in time posed logistical problems:

We were building the model on one end of the stage and photographing it on the other with a black curtain between the two — that was the unique approach to doing the work. We had three crews working 8-hour shifts in order to get that work done.

The situation was complicated because the camera had to record several passes over the model at slow speeds. Some of the passes took as long as 18 hours, and if the motors failed (which they often did) they had to be recorded again from the beginning.

New scenes

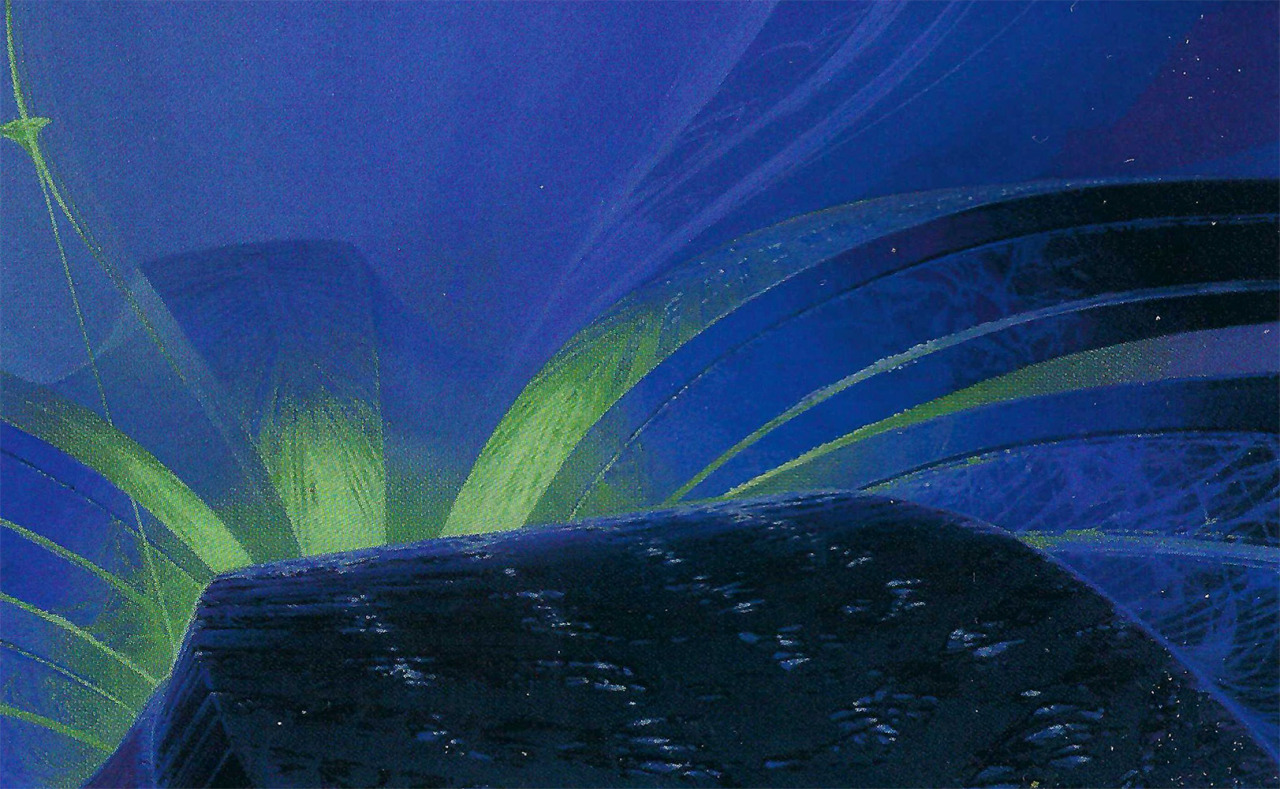

Trumbull’s team, handling the interior of V’Ger, considered several approaches — possibly using matte paintings or some kind of laser-scanning effect — before settling on a conventional model.

When it was filmed, the model was filled with smoke to give it a sense of scale. The walls were originally illuminated with miniature light bulbs, which were built into the model. However, when it came to filming they were too big to be convincing. Greg Jein, who had built the model, suggested a solution: drill hundreds of holes in the model and run fiberoptic lights behind them.

The major reason Trumbull took on the shots inside V’Ger was that he was also filming a new sequence in which Spock explored the inside of the vast machine. His Spock spacewalk replaced the memory wall sequence that Abel studios had planned, and which had been filmed during first-unit photography. Trumbull did not feel he could make the sequence work. The wire work that had been filmed on the stage was awkward and unwieldy. There were problems with reflections in the spacesuit faceplates.

Trumbull convinced Director Robert Wise to let him shoot a new sequence, which he designed himself. The storyboards were worked up by Tom Cranham, with several artists, including McCall and David Negrón, developing concepts for the things Spock would see. The spacesuits were completely redesigned and built at Apogee.

The final effect — when V’Ger disappears leaving the Enterprise in orbit around Earth — was specially designed so that it only expanded horizontally, insuring that it could not be mistaken for a conventional explosion.

Incredibly, all these shots were completed in time for the movie’s premiere and the world was so impressed with what it saw that the Trumbull/Dykstra team was jointly nominated for an Academy Award.

12 comments

Submit comments by email.