The Making of Star Trek: Phase II

After several attempts to bring Star Trek to the silver screen, Paramount decided in 1977 to produce a second television series, called Phase II.

Barry Diller, Paramount’s president, had been concerned about the direction in which Chris Bryant and Allan Scott were taking the franchise with their script for the proposed movie Planet of the Titans. He turned to Gene Roddenberry and suggested it was time to take Star Trek back to its original context: television.

Flagship

When Phase II was officially announced on June 10, 1977, fans learned it would become the flagship of a Paramount television network.

The advantage of setting up a network was obvious: the studio was cutting out the middleman.

As a content provider to the networks, Paramount would produce a series, license it to a network, often at a loss, and then watch as the network sold the series to advertisers at a profit. Only when, and if, the series went to syndication would the studio have a chance to earn extra money.

But, in the case of licensing a Paramount-produced series to a Paramount-owned network, one division of the company would be selling to another and all the money would stay in the family.

That offered the possibility that a series could at least break even, without the long wait until syndication. And syndication could be a never-ending stream of income, as Paramount’s “79 jewels” proved year after year.

Those 79 were, of course, the original Star Trek episodes.

Another advantage was that Star Trek attracted television’s most vaunted demographic: men aged 18 to 34.

The plan was for an all-new Star Trek television series to anchor the new Paramount network. Star Trek: Phase II was officially a go. A two-hour made-for-TV movie would lead the way in February 1978, to be followed each week by a brand new, one-hour episode, airing between 8 and 9 at night.

Gathering a team

Gene Roddenberry was ecstatic. After five year of false starts, all the pieces were at last falling into place. It was time to be Star Trek’s lightning rod again and gather a team.

Roddenberry hired two producers. Robert Goodwin, who was an assistant to Paramount’s head of television production, would be responsible for the technical side of things. For the writing side, Roddenberry hired noted novelist and screenwriter Harold Livingston.

Neither had worked with Roddenberry before. Goodwin was meant to produce made-for-TV movies for Paramount and later said he was “strong-armed” into doing Star Trek. Livingston described himself as “totally unwashed” when it came to Star Trek, but he and Roddenberry hit it off.

We had similar backgrounds. We had both been in the Air Force during the war and we both worked for civilian airlines after the war.

Livingston persuaded Roddenberry to promote his assistant, Jon Povill, to story editor.

“Harold had not been very familiar with the old series at all,” Povill recalled years later, “and kind of relied on me to monitor whether something fit with Star Trek or not.”

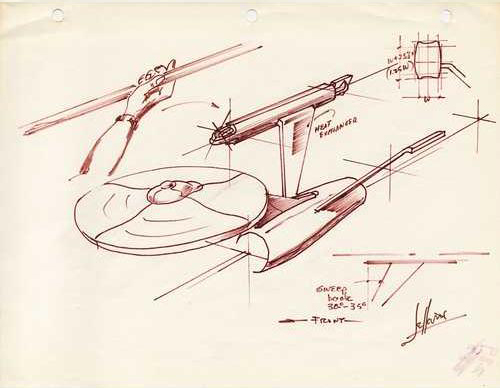

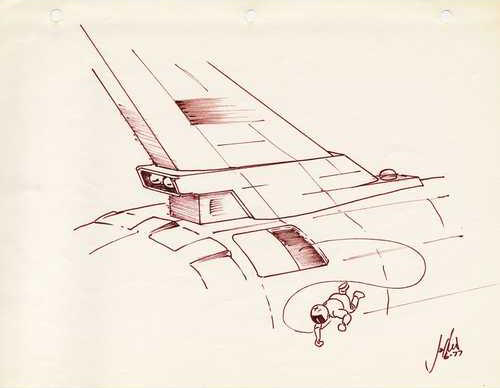

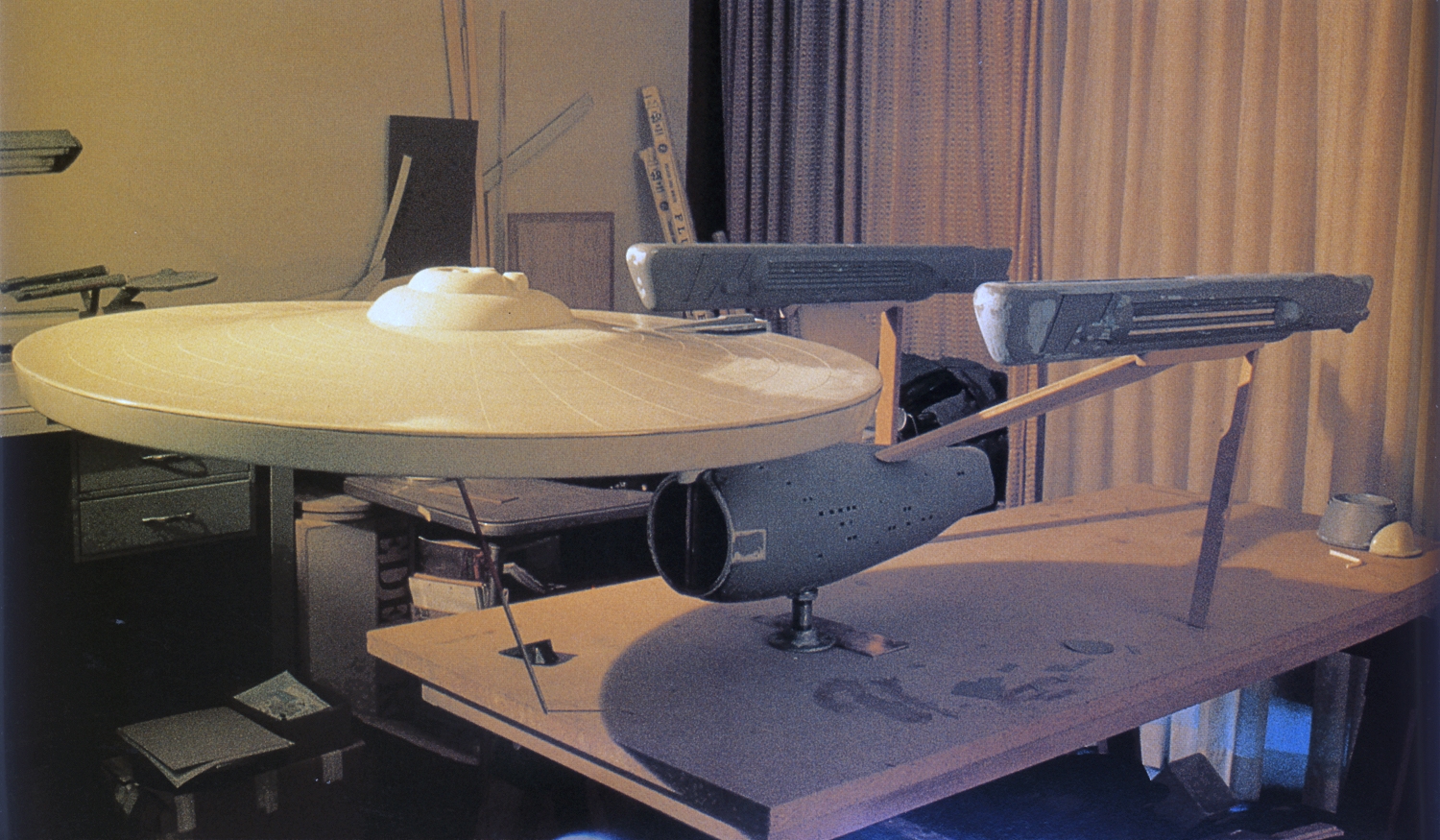

A final team member Roddenberry enlisted was an old friend: Matt Jefferies, Star Trek’s first art director. He was working on Michael Landon’s hit series Little House on the Prairie at the time and was reluctant to give it up for the sake of thirteen new Star Trek episodes. But Roddenberry was adamant. Only Jefferies, he said, could update the Enterprise. With Landon’s blessing, Jefferies joined the Phase II crew as a “technical advisor”.

Landon made clear that Jefferies’ work for Star Trek could not get in the way of his responsibilities on Little House. That’s how Jefferies came to recommend his friend Joe Jennings as the new Star Trek art director.

Other Star Trek veterans who joined the crew included Mike Minor in the Art Department and William Ware Theiss as costume designer. Lee Cole joined the graphics team. She would go on to have a big influence on the sets of the first two Star Trek motion pictures.

Cast

The bigger challenge was getting the cast back together. William Shatner demanded more money. Leonard Nimoy was unwilling to return at all.

In order to fill the void created by Spock’s absence, three new characters were added — and hopes were that Nimoy might be persuaded to occasionally reprise his role in guest appearances.

Replacing Spock on the bridge would be Lieutenant Xon, a young and bright Vulcan science officer. Unlike Spock, Xon would have virtually no knowledge of the human equation. He would try to imitate humans in order to get closer to the crew. “We’ll get some humor out of Xon trying to simulate laughter, anger, fear and other human feelings,” Roddenberry wrote. (Sound like any androids we know?)

The second new character was Commander Will Decker, son of the Commodore Matt Decker who was killed in “The Doomsday Machine”. Contrary to his antagonist relationship with Kirk in The Motion Picture, the Phase II Decker would greatly admire the captain. The character was created with the possibility that Shatner might eventually become too expensive for the show in mind.

The final addition was Lieutenant Ilia, a bald Deltan, whose race was marked by its heightened sexuality. She would have empathetic abilities and a history with Decker, foreshadowing the character of Counselor Troi.

Povill argued that the new characters helped tremendously in finding new stories to tell:

I think the biggest challenge was coming up with things that weren’t repeats of ideas which had already been explored.

He particularly liked Xon.

I thought there was something very fresh in having a nice young Vulcan to deal with, somebody who was trying to live up to a previous image. That, to me, was a very nice gimmick for a TV show that was missing Spock.

Going boldly

Television had changed a lot since The Original Series aired more than a decade ago. Roddenberry told Starlog magazine in March 1978 that the second series could be bolder than the first:

The audience is certainly more sophisticated and able to reach their minds out further. The audience is ready for statements on sex, religion, politics and so on, which we never would have dared to make before.

In his guide to Star Trek writers, Roddenberry advised:

We will use science fiction to make comments on today, but today is now a dozen years later than the first Star Trek. Humanity faces many new questions and puzzles which were not obvious back in the 1960s, all of them suggesting new stories and themes.

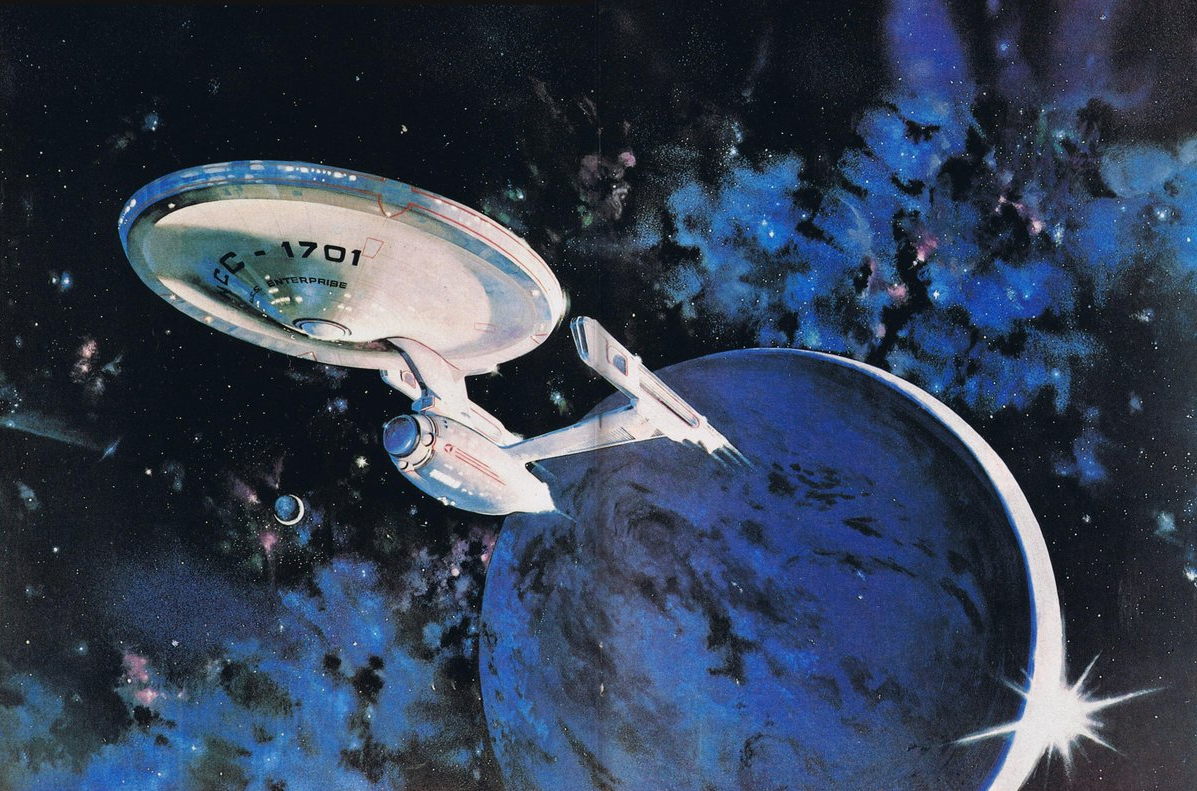

But some things would not change. Star Trek was still a show about people. Science and gadgetry could not distract from the plot. Captain Kirk and his crew were heroes and should always react as such. Their home base was the Enterprise.

A movie after all

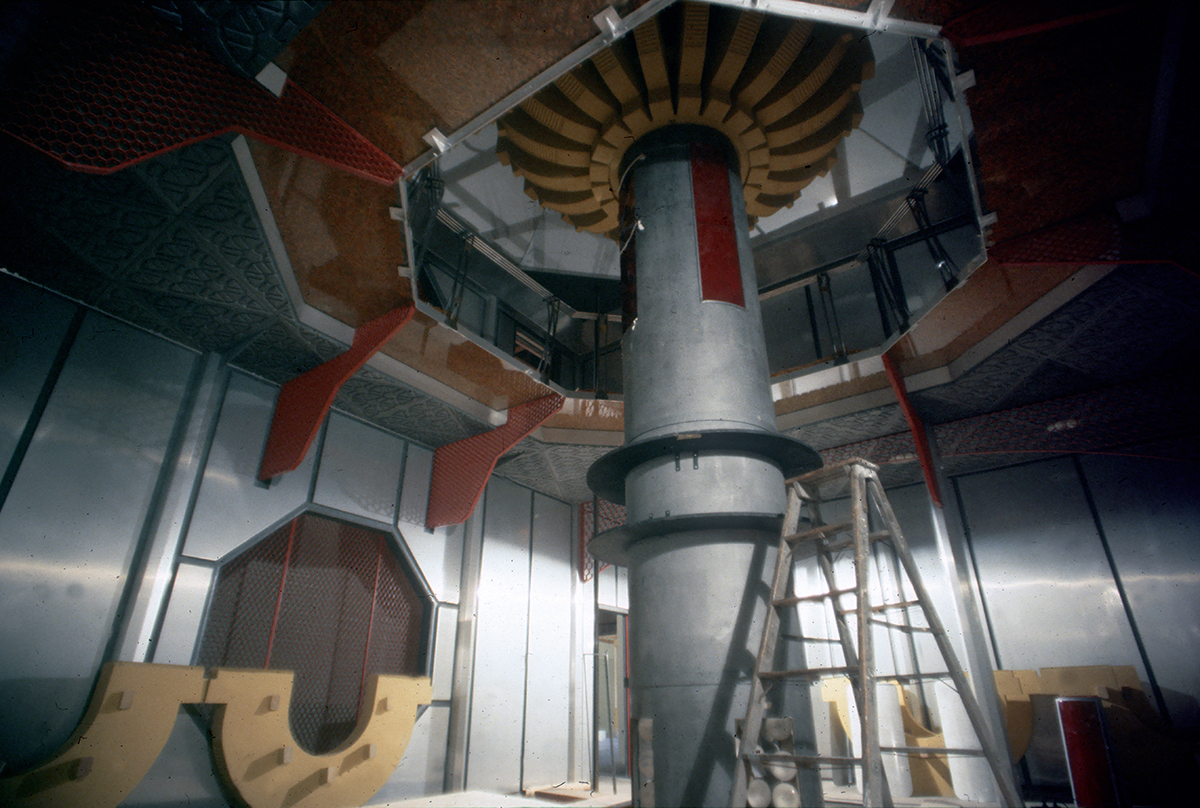

Jefferies was upgrading the Enterprise. Sophisticated new aluminum phasers, following the same design as the original wood-and-plastic ones, were being built, some with working strobe lights and detachable battery packs. Sets were going up on Paramount’s Stage 9. Goodwin reported:

All frames and platforms have been built for the bridge… By tomorrow we will have a layout on the stage floor for the corridor and by the beginning of next week we will start framing and constructing the corridor walls.

Livingston had recruited a slew of science-fiction writers: Margaret Armen, Alan Dean Foster, Arthur Heinemann, John Meredyth Lucas, James Menzies, Theodore Sturgeon, Worley Thorne, Shimon Wincelberg. Only Sturgeon ultimately didn’t turn in his story.

In addition, he was receiving unsolicited pitches and scripts from many more authors. “They keep coming in and the response from writers is totally overwhelming,” Livingston reported in a memo. Most were turned down and Star Trek quickly developed a reputation as the “hardest sell in town”.

Heinemann pitched, and Foster wrote, the show’s pilot, “In Thy Image”. It incorporated Goodwin’s suggestion that, for the first time on Star Trek, Earth would be directly threatened. If that was the case, then the Enterprise needed to be close to Earth — make that, still in Earth orbit — because… it was just finishing its refit!

A meeting was called for August 3, to be attended by Goodwin, Livingston and Roddenberry, as well as studio executives Michael Eisner, Arthur Fellows and Jeffrey Katzenberg. At the meeting, Goodwin pitched “In Thy Image”, hoping it would receive Eisner’s blessing as the Phase II pilot.

The meeting didn’t go as expected. Eisner was so excited by the story, he said, “We’ve been looking for the feature for five years and this is it.”

Goodwin recalled years later that Eisner slammed his hand on the table — “and that was when it happened.” Less than a month after Phase II had been announced, it was canceled. Star Trek was going to be a movie after all.

The catch was, nobody in the meeting could talk about it. New deals would have to be negotiated with the cast, with producers, with Gene Roddenberry himself. New budgets would have to be calculated. If, for whatever reason, a movie could not be made, Paramount would face the embarrassment of needing to publicly reverse its decision yet again. Phase II was dead. But it would be five months until the body stopped twitching.

Until then, a group of dedicated, talented men and women toiled on to create a series they and millions of fans could be proud of, never knowing that the studio had little intention of making it.

14 comments

Submit comments by email.