A Grittier Star Trek: Creating Deep Space Nine

The Next Generation had proved the resilience and appeal of the Star Trek universe. The franchise was not dependent on Kirk and his famous first crew for its success. The future of Star Trek seemed unlimited.

But after five years, Paramount executives could see their own future was constrained. It made little economic sense to continue most television shows for more than five or six seasons. Costs increased, storylines became exhausted and the syndication market would fill with too many episodes chasing too few time slots. From a business point of view, The Next Generation’s days were numbered.

Everyone’s instincts said that Star Trek hadn’t saturated its market. In Paramount offices, the idea of a third television series was being discussed.

The Next Generation had shown that Star Trek could thrive without its original characters. Could a new series survive without a ship?

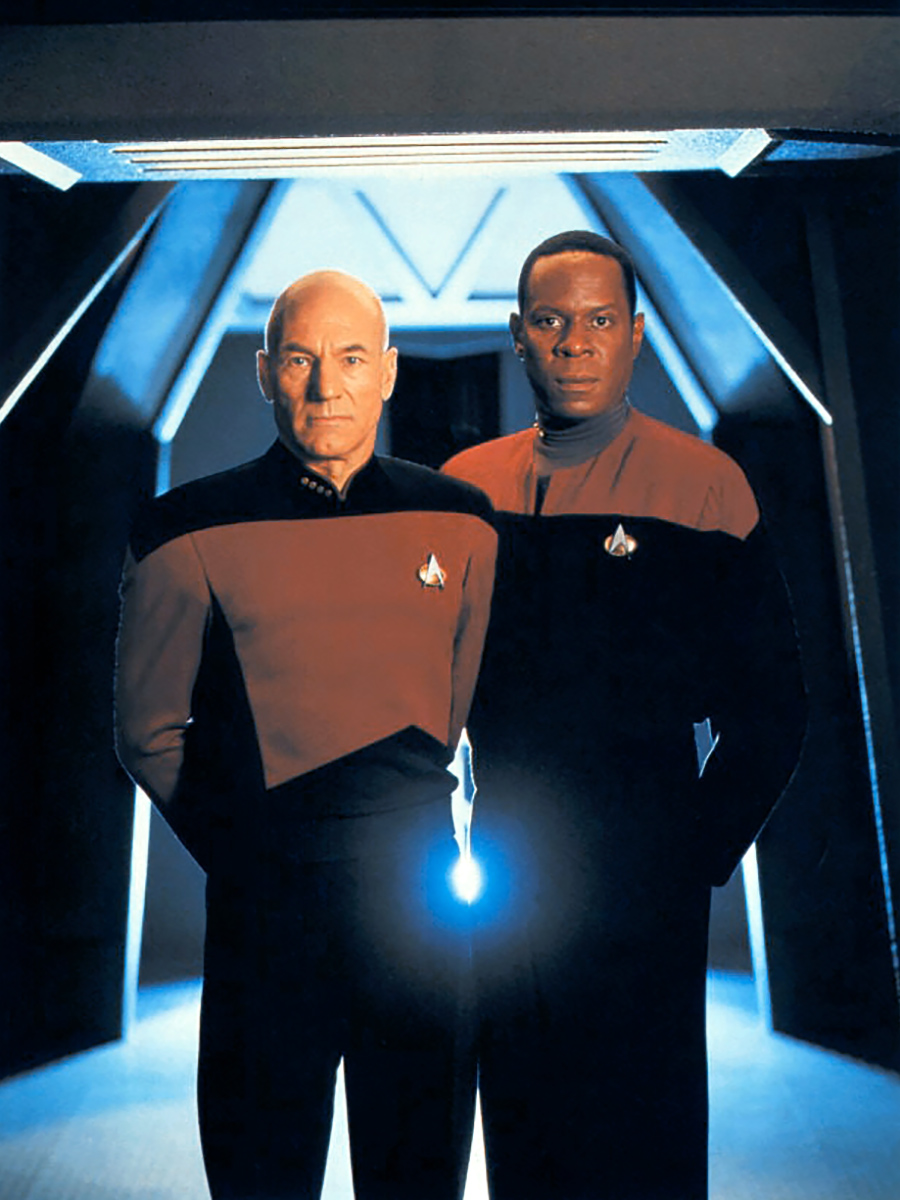

Rick Berman, Gene Roddenberry’s handpicked successor, and Michael Piller, The Next Generation’s most influential writer, created Star Trek: Deep Space Nine with that challenge in mind.

A darker show

For a quarter century, one of Star Trek’s strengths had been the detailed universe through which the two Enterprises had traveled. Now the franchise’s guides decided it was time to venture out into that universe, choose a pocket of it and locate an entire series there.

Sadly, the announcement of the new series came just after Gene Roddenberry’s death in late 1991. The timing fueled speculation that had Roddenberry lived, Deep Space Nine might not have. Suspicions along those lines were raised particularly after description of the new series filtered out. “It’s going to be darker and grittier than The Next Generation,” Berman told Entertainment Weekly in March 1992. “These characters won’t be squeaky clean.”

Berman and Piller had started developing the new series in October 1991. They decided it should take place in the same time period as The Next Generation in order to take full advantage of the Star Trek universe that had been established so far.

At the same time, Deep Space Nine was a means of escaping the somewhat limiting constraints of Gene Roddenberry’s original Star Trek concept. According to Berman, they “set about creating a situation, an environment and a group of characters that could have conflict without breaking Gene’s rules.”

We took out characters and placed them in an unfamiliar environment, one that lacked the state-of-the-art comfort of the Enterprise and where there were people who didn’t want them there.

A shambles

Piller drew on “Encounter at Farpoint”, The Next Generation’s first episode, for the Deep Space Nine pilot. He delayed the introduction of key characters until later in the story. The captain was put in a position of having to explain or justify humanity to an alien race.

Piller managed to give the concept — used so often in Star Trek — an interesting spin: Sisko had to communicate with aliens who did not experience time in linear fashion.

But the first drafts had too much talk while the transition to Federation command of the space station was bland.

Deep Space Nine was originally envisaged as a dilapidated, seedy space station with technology that lagged behind Starfleet’s. This notion was scrapped in favor of a more high-tech look, which in turn forced Piller to rewrite. He decided that the departing Cardassians would have ransacked the place, leaving a shambles for Sisko to rebuild. That involved convincing the merchants of the Promenade and other inhabitations of the station to stay and pull things back together.

“Emissary” ended up costing $12 million, $2 million of which was spent on erecting the standing sets of the series.

Breaking taboos

Deep Space Nine’s other central race — the Bajorans — had been introduced in The Next Generation. Viewers knew their world had been conquered by the fascist Cardassians and stripped of its resources. “Emissary” explored Bajoran culture further, which also meant exploring religion, a topic that had seldom been portrayed positively on Star Trek before.

As Pillar put it, “One of the primary goals in making this series is to do something we didn’t have the opportunity to do in The Next Generation.”

Sisko’s character was another change. “We wanted to create a new kind of Star Trek hero,” said Piller, “a man who is not just the Starfleet officer who has given up family for career, like Picard; not like Kirk, who’s one of the boys on a great adventure. He is a man who had a family and has lost a wife he loved and must raise a son.”

Avery Brooks, who played the commander, said his “very human” character avoided the military strictures adorning many Starfleet officers:

So much of the military veneer is not there. He expresses what he feels. He isn’t particularly interested in being here. He’s following orders. He’s worried about raising his son in this environment. This station has been devastated.

Star Trek ethos

Berman and Pillar took quite a few risks, but they managed to distill Star Trek to its core ethos. The crew was united under one flag. The increasingly complex consistency of future history and technology provided a rich background for storytelling.

“It’s still Gene Roddenberry’s vision,” according to Pillar.

It has an optimistic view of mankind in the future. Reason and dialogue and communication are still the key weapons in the fight to solve problems.

The fans agreed. Deep Space Nine was an instant success, sharing many viewers with The Next Generation, adding new viewers of its own, and demonstrating once and for all the deeply appealing richness of what Gene Roddenberry had wrought. It wasn’t the characters. It wasn’t the ship. Star Trek was a state of mind. And millions still wanted to share it.

1 comment

Submit comments by email.