Creating Planet Vulcan

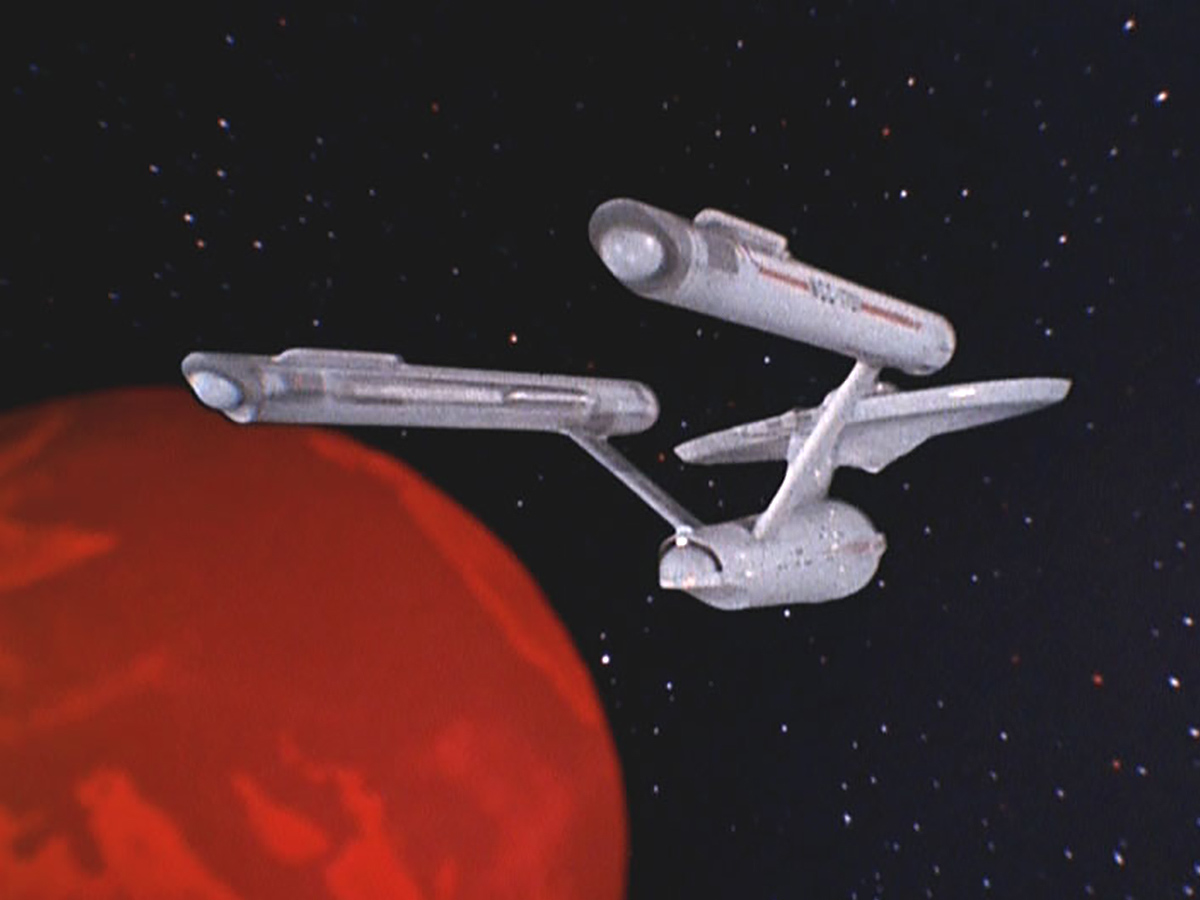

Spock’s popularity had made Star Trek fans eager to catch a glimpse of his home world. When the Enterprise finally visited Vulcan in “Amok Time”, NBC executive Stan Robertson said the episode should reveal as much of the planet as possible:

[Vulcan has] been built as such a mystery throughout our series that unless we establish more of the planet than is outlined here […] we will indeed be “cheating” our viewers.

Unfortunately, the show didn’t have the budget to meet Robertson’s requirement. Writer Dorothy C. Fontana told Star Trek: The Magazine in an interview that was published in July 1999 that they could only give viewers “a flavor, a feeling” of the planet.

Amok Time

In “Amok Time”, Spock must return to Vulcan to cope with the onset of pon farr.

The script describes Vulcan as “a landscape of drifting sand stretching away to a distant saw-toothed line of mountains jutting up at the edge of the far horizon.” In one scene, Dr McCoy remarks that he now understands the phrase “hot as Vulcan.” The sky is shown to be red.

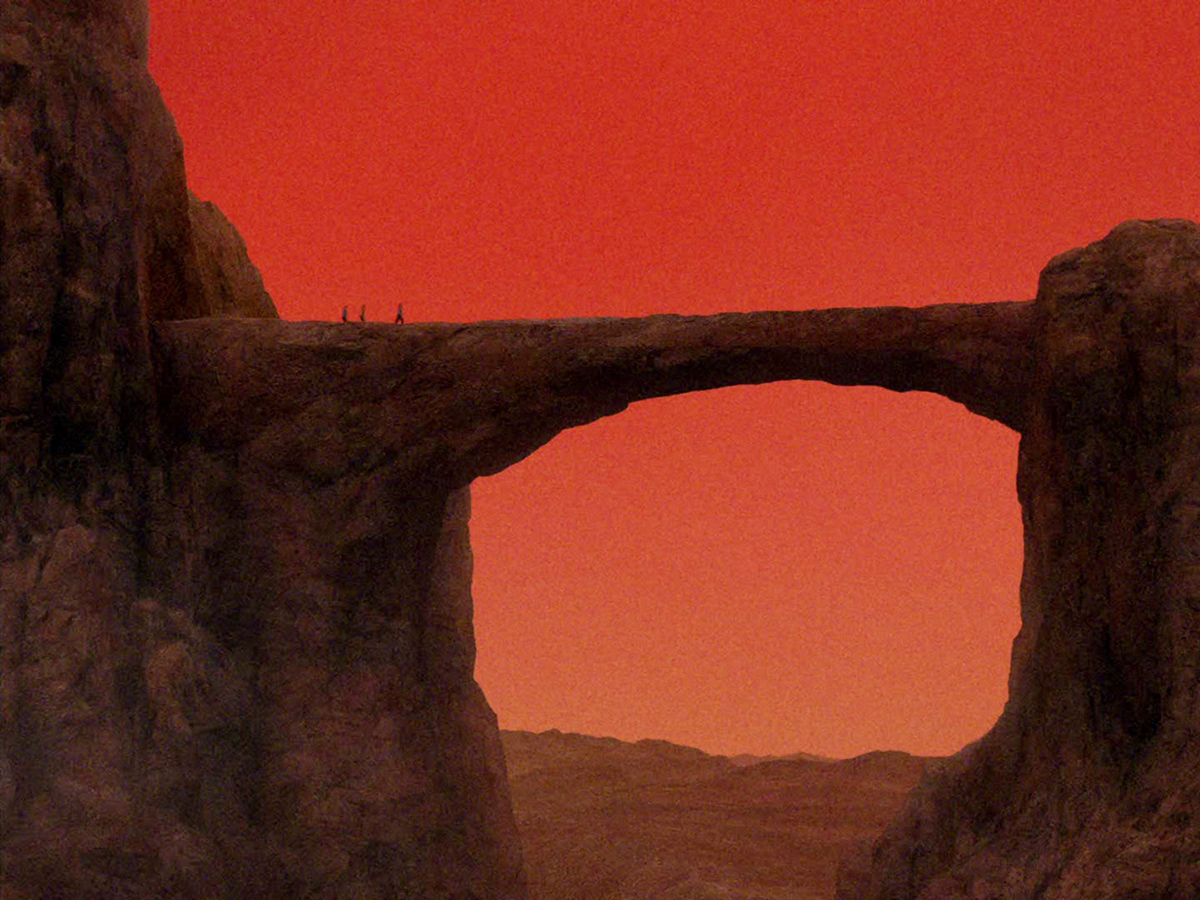

The only set the show could afford to build was a ceremonial temple-like area, where Spock would be forced to battle Kirk to the death. Writer Theodore Sturgeon came up with a way to make it relatively inexpensive to build while still looking alien: Vulcan culture, he argued, was highly advanced but had retained an appreciation for craftsmanship. The grounds could therefore look primitive:

A fairly level arena area. Rocks around the edges give a half-natural, half-artifact aspect, as if the wind or rain had curved something like a Stonehenge, or reduced a Stonehenge to something like this. Within this rock area is a Vulcan-made “open temple.” In history, perhaps it was once a shrine. There are two high arches of stone, a level stone floor an open fire-pit toward the “rear” as we look at it.

When time came to remaster “Amok Time” in 2007, Visual Effects Producer Dave Rossi initially struggled to find a way to make the scenes more interesting.

“I soon realized that the number of times we see the red sky behind the actors was going to make it impossible to treat it in any way,” he told Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection in 2016.

As I was flying back to Los Angeles, it dawned on me that maybe the reason we only see red sky is because the ancient ceremonial grounds were high up in the sky, like on a mountain. I had a friend sketch the idea that this arena of rock had two natural stone bridges that connected it to mountain chains on each side.

This was inspired by the look of Mount Seleya in Star Trek III. A matte painting of a Vulcan city in the far distance was also added.

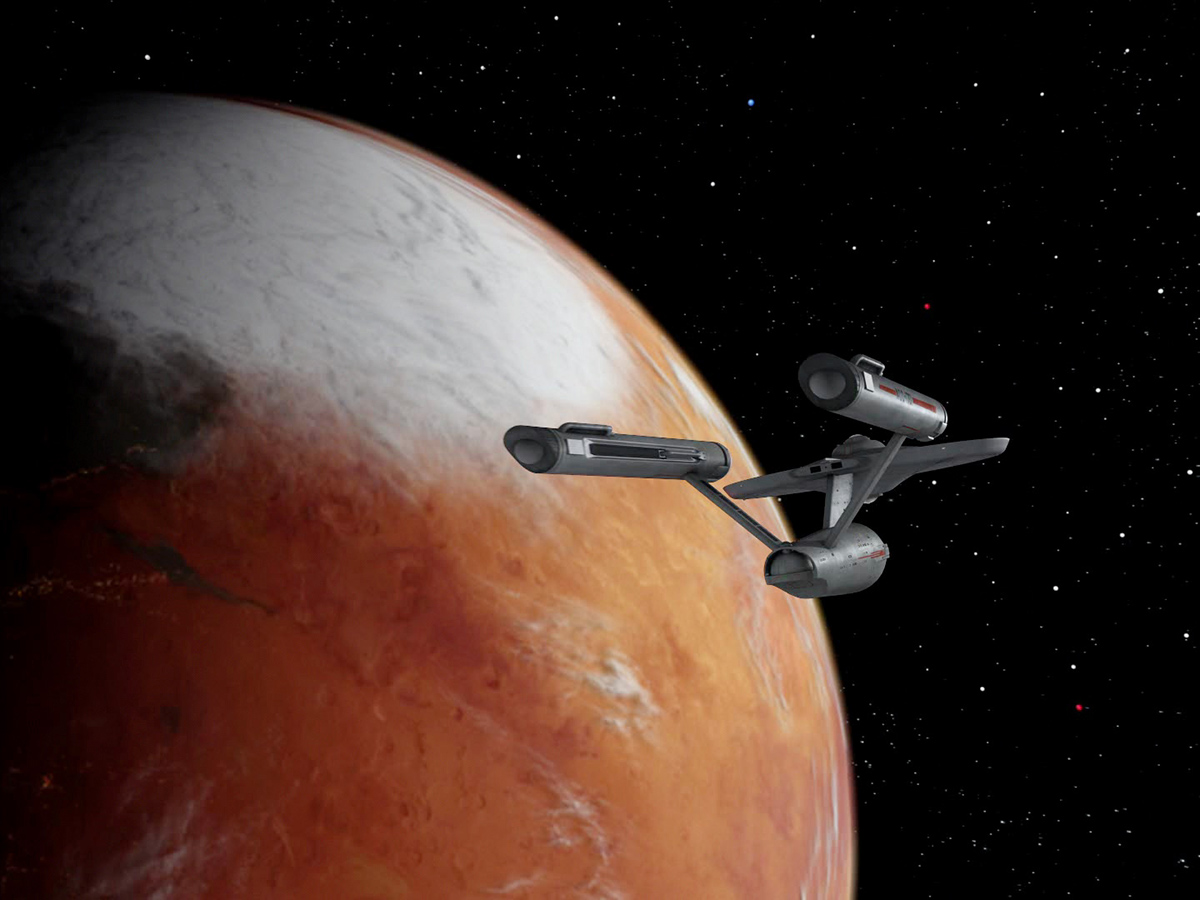

The Motion Picture

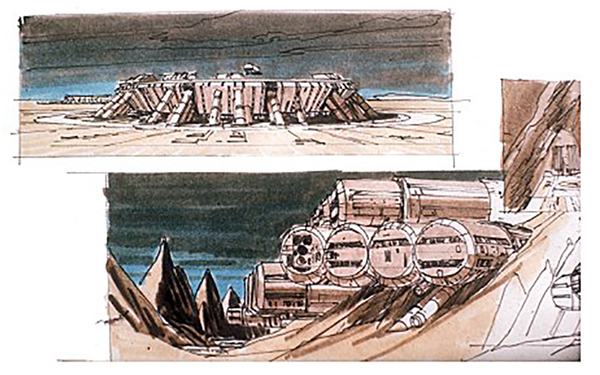

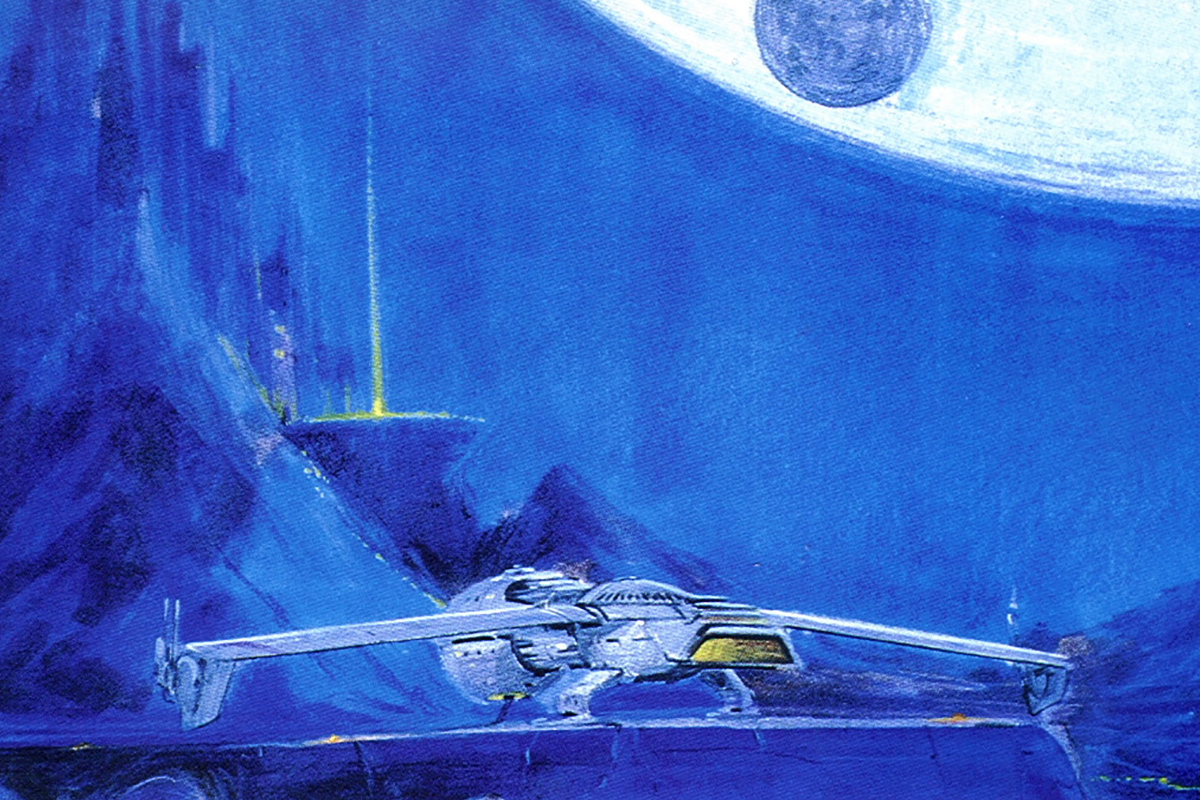

Vulcan didn’t appear during the rest of The Original Series. It might have featured in the aborted Star Trek movie Planet of the Titans. Ralph McQuarrie, of Star Wars fame, produced several concept arts showing Vulcan as a desert planet where the population lived underground.

When Planet of the Titans became Star Trek: Phase II, Vulcan was written out of the script for the pilot “In Thy Image” because Leonard Nimoy wouldn’t return as Spock. When Phase II became The Motion Picture, and Nimoy was persuaded to return, Vulcan was written back in.

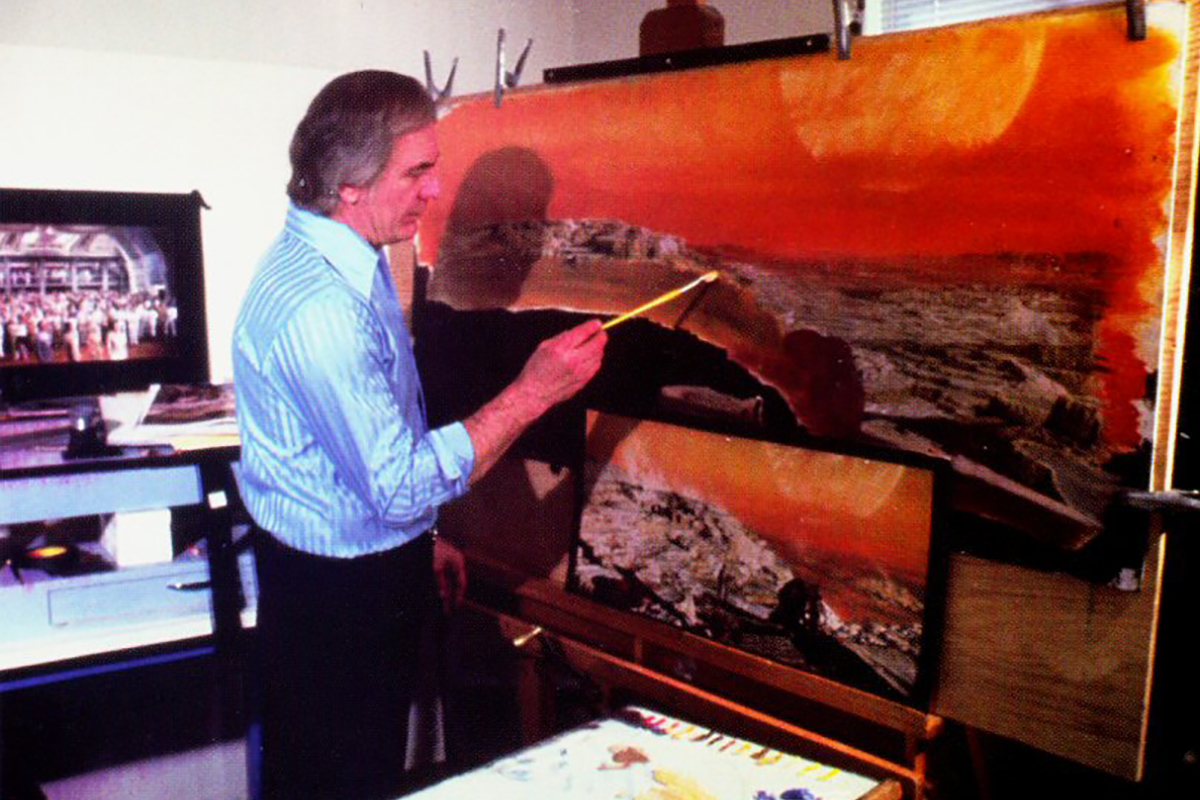

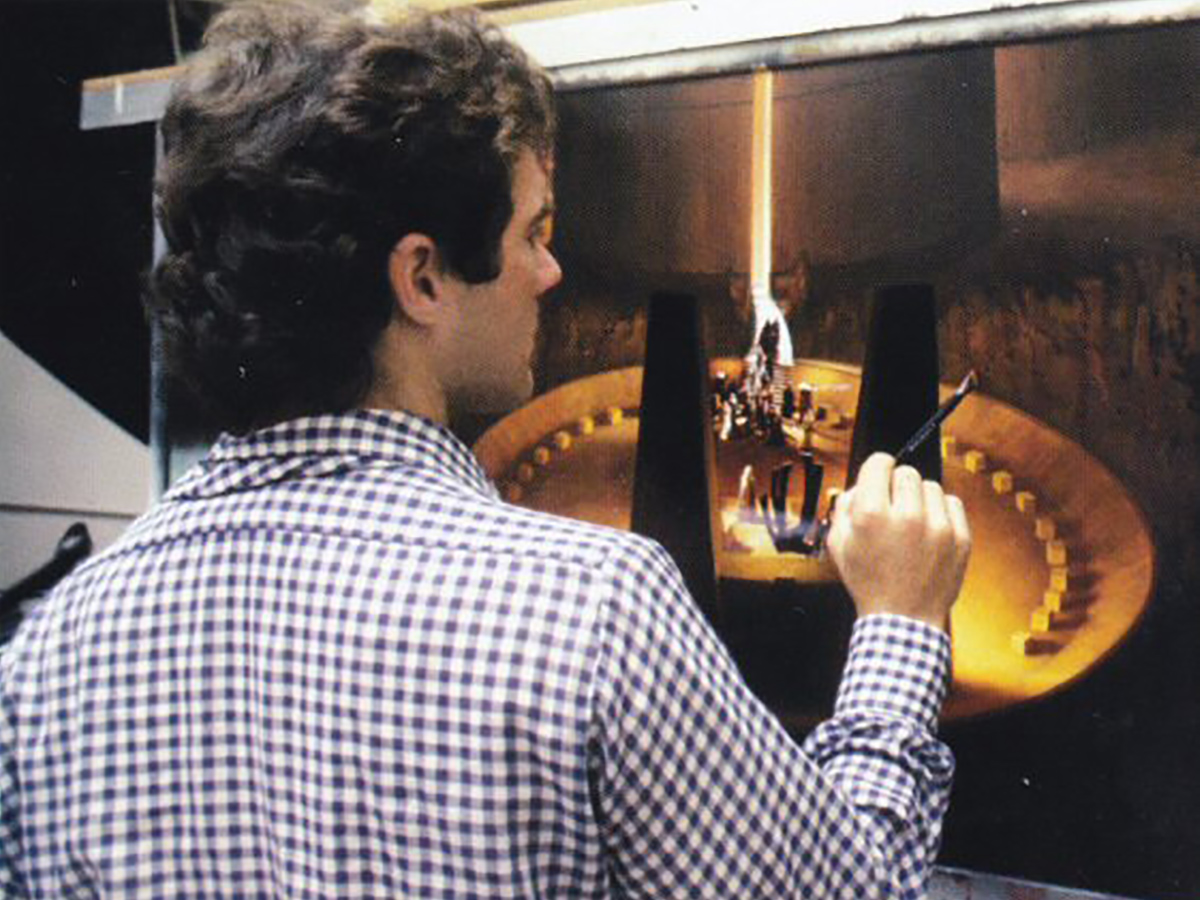

Director Robert Wise and Production Illustrator Maurice Zuberano looked to various places on Earth for inspiration, including Afghanistan, Tibet and Turkey. At one point, they considered shooting the scene on location in Turkey, but this was too expensive. Instead, part of the scene was shot in Yellowstone National Park, part on the Paramount lot, and the rest filled in by Matthew Yuricich’s matte painting.

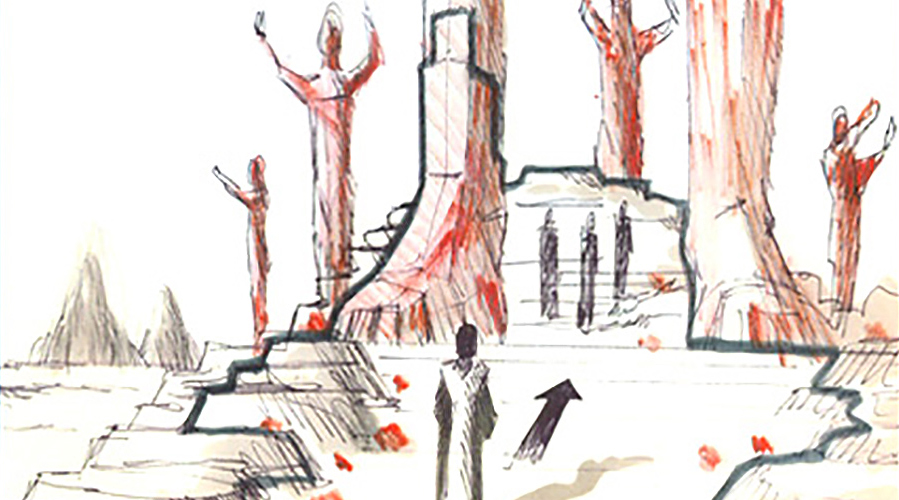

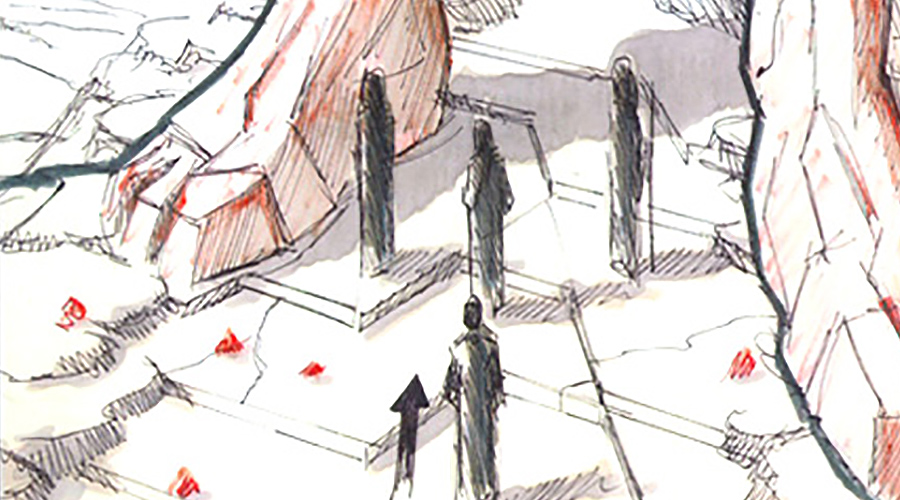

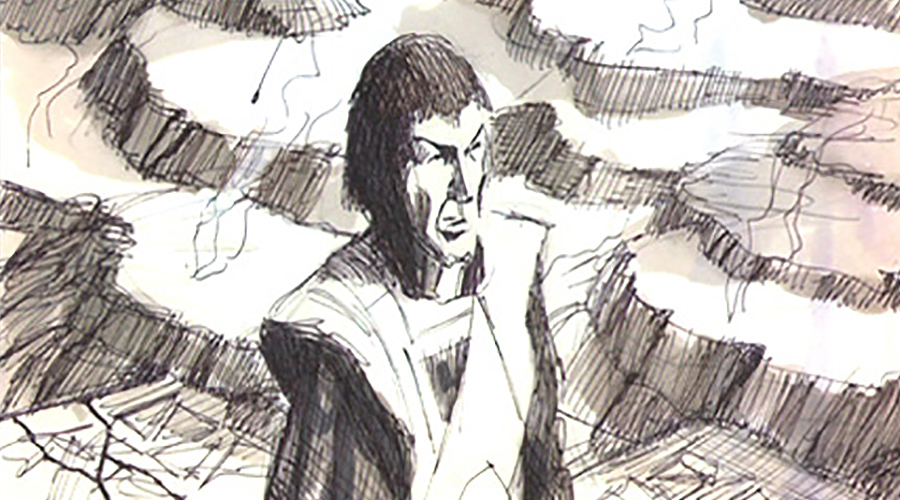

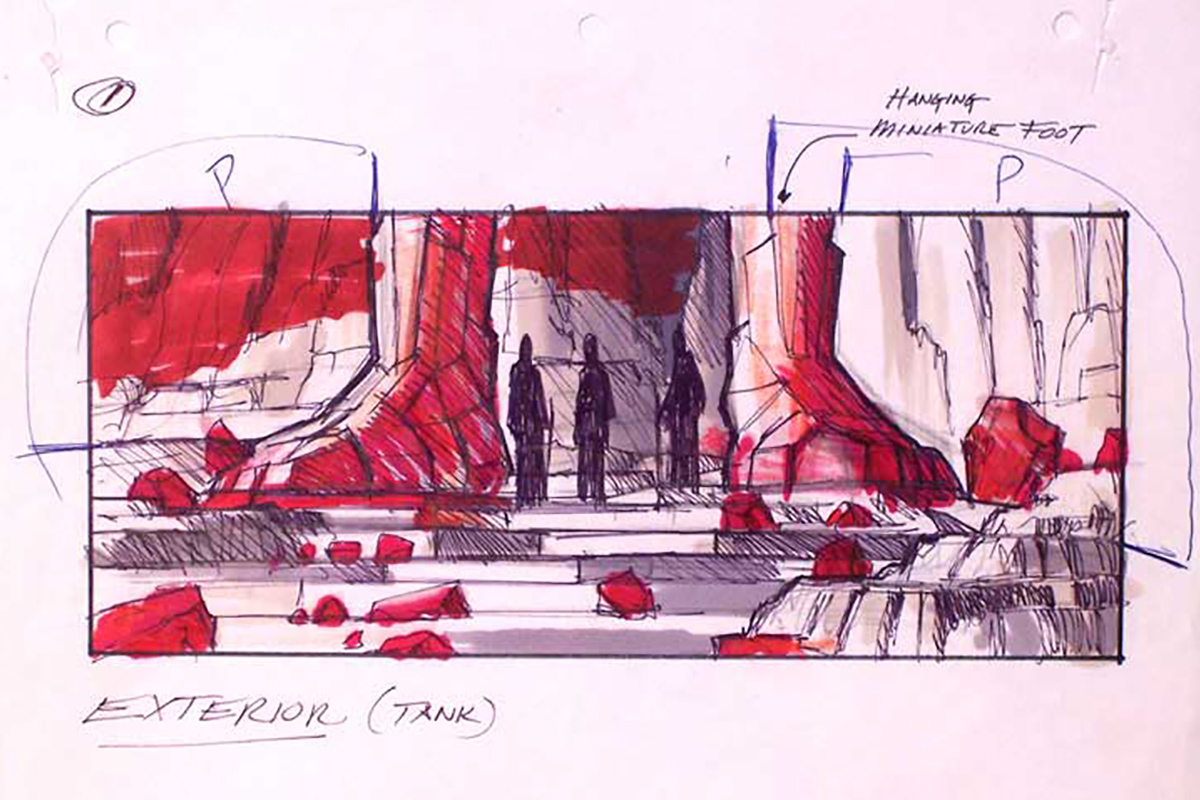

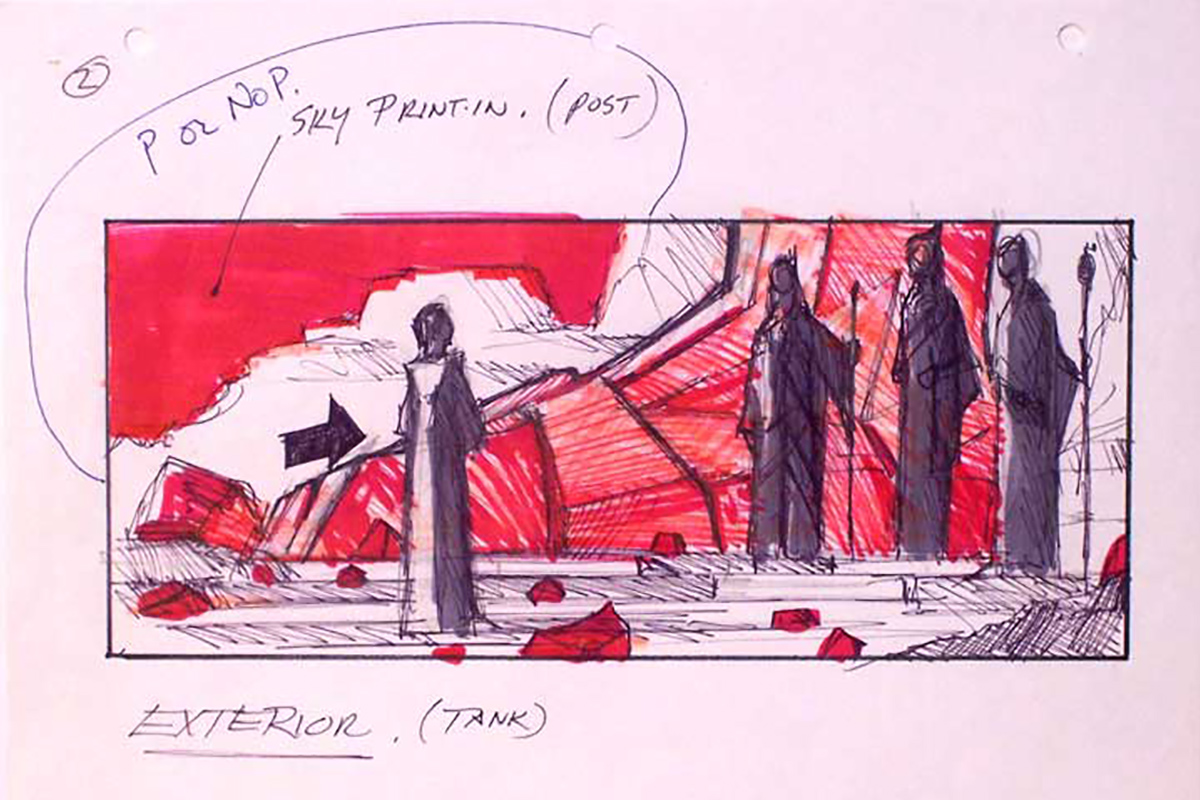

Robert T. McCall provided a concept of a Vulcan temple that wasn’t used. Mike Minor drew the storyboards.

The scene was redone for the 2001 Director’s Edition. We get a better view of the enormous statues behind the actors and the sky was changed from a starry black to orange, corresponding with the look that was established in Star Trek III.

The Director’s Edition also fixed one of Star Trek’s most infamous errors. In “The Man Trap”, Spock clearly tells Uhura that Vulcan has no moon, yet two celestial bodies appear in the sky in the theatrical cut of The Motion Picture. These were removed.

The 2022 4K cut of The Director’s Edition made the scene brighter. Producer David C. Fein told StarTrek.com, “This certainly makes sense, since you can see [Spock] block sunlight from his eyes in a previous shot.”

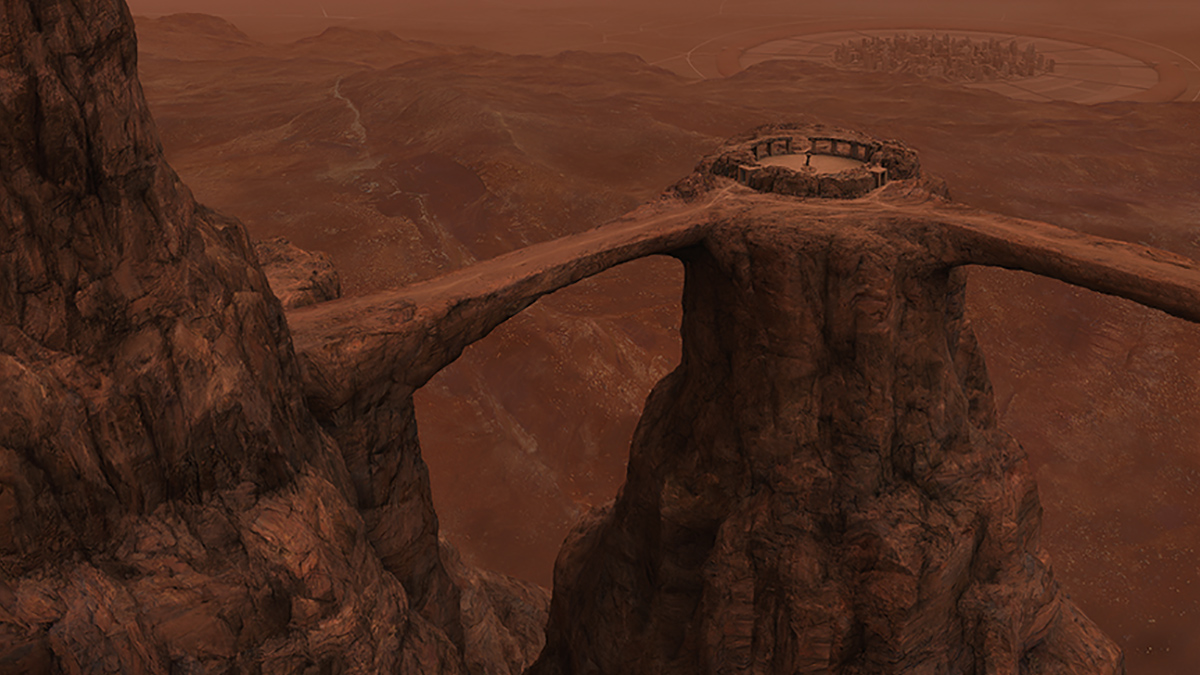

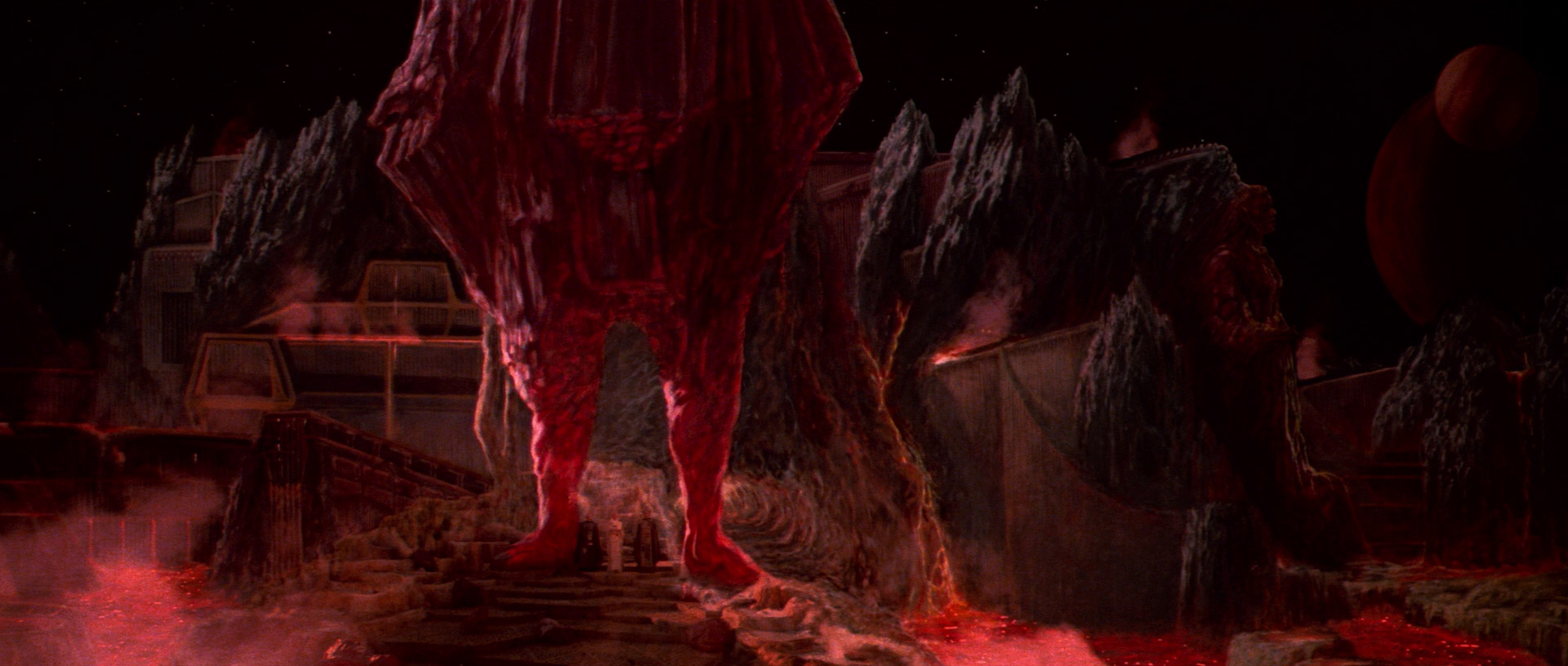

The Search for Spock

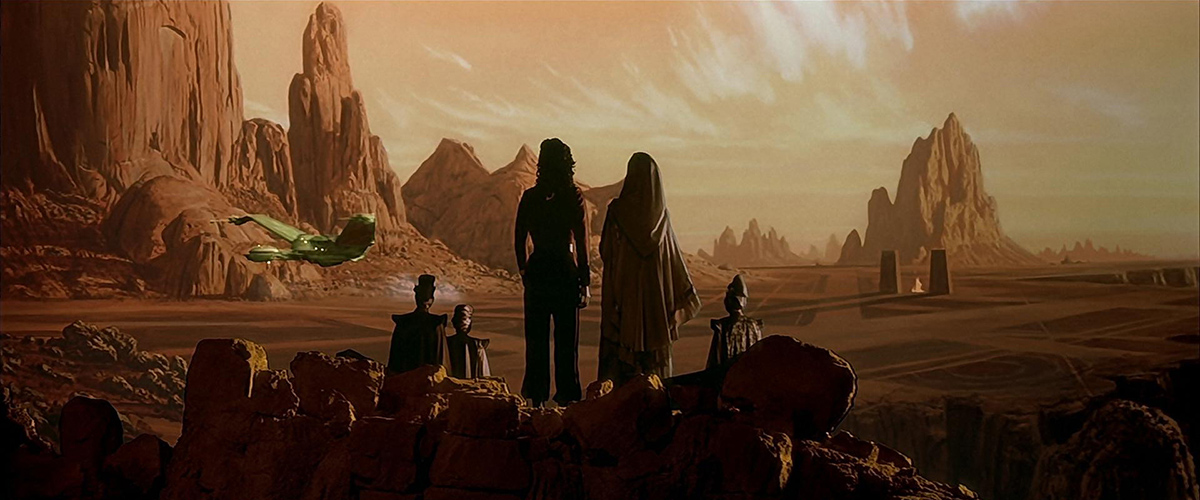

Producer Harve Bennett and Director Leonard Nimoy agreed that Star Trek III called for a grander scale than Vulcan’s previous appearances. Charles Correll, the film’s director of photography, argued for shooting scenes in Nevada to avoid a “phony” look. He was also careful to make sure the planet would appear with an orange sky.

The Bird of Prey landing site was ultimately filmed on location at Occidental College in Los Angeles. Other scenes combined live-action footage with matte paintings.

Visual Effects Supervisor Ken Ralston was happy with the result, telling Cinefex magazine in 1984 that the Vulcan scenes had a “dreamlike” quality to them.

[T]he continuity of the sets and the effects and the color work very well together — it fools you into believing it’s much more real than it would have been if they had shot it in the Mojave Desert and then we’d have cut to a painting with a whole different set of values.

Nimoy, too, was pleased with the opportunity to depict the planet on such a grand scale.

To the director, the delight of the visuals of the Vulcan scene, especially by a Vulcan director.

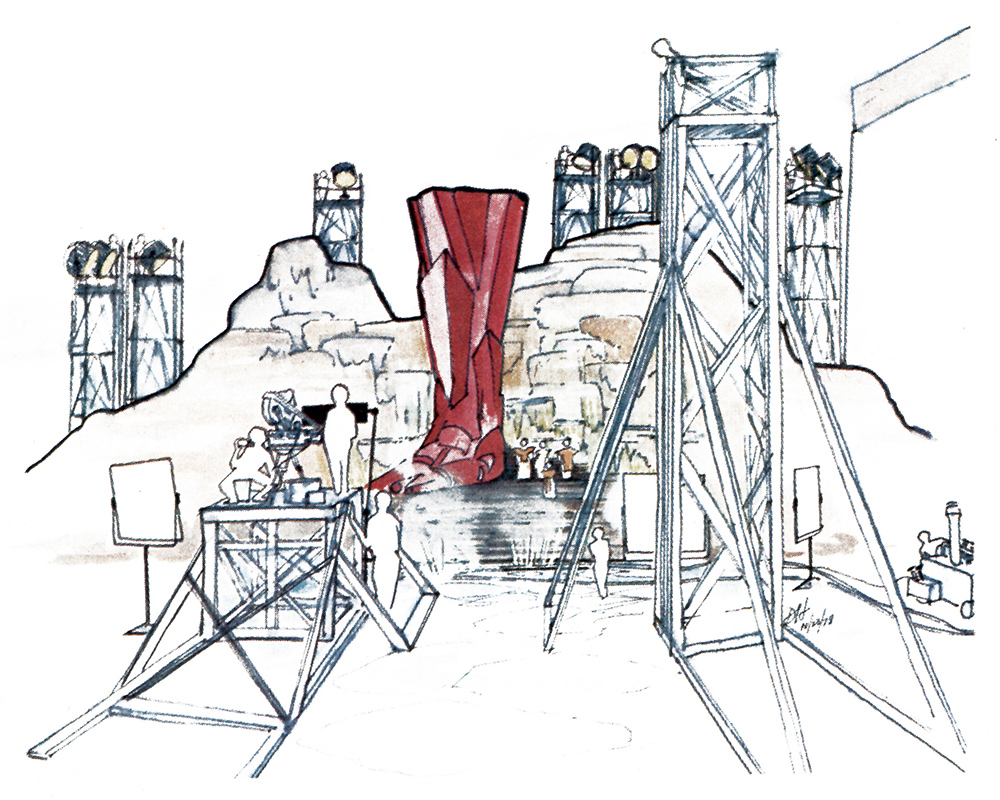

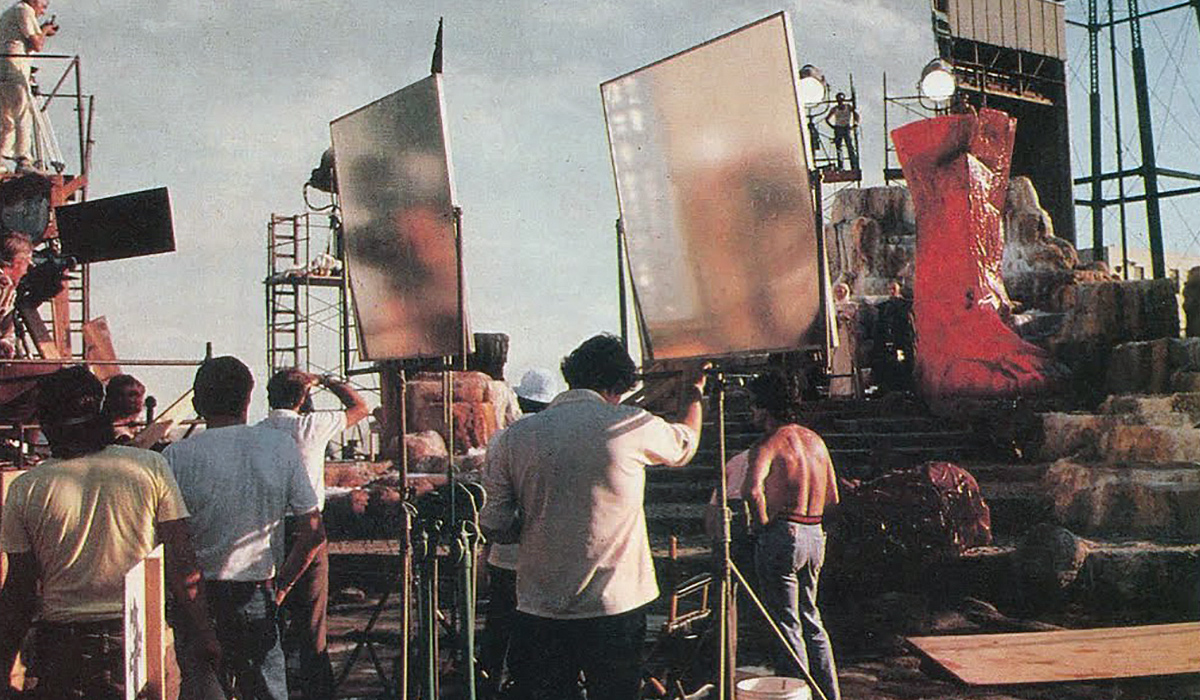

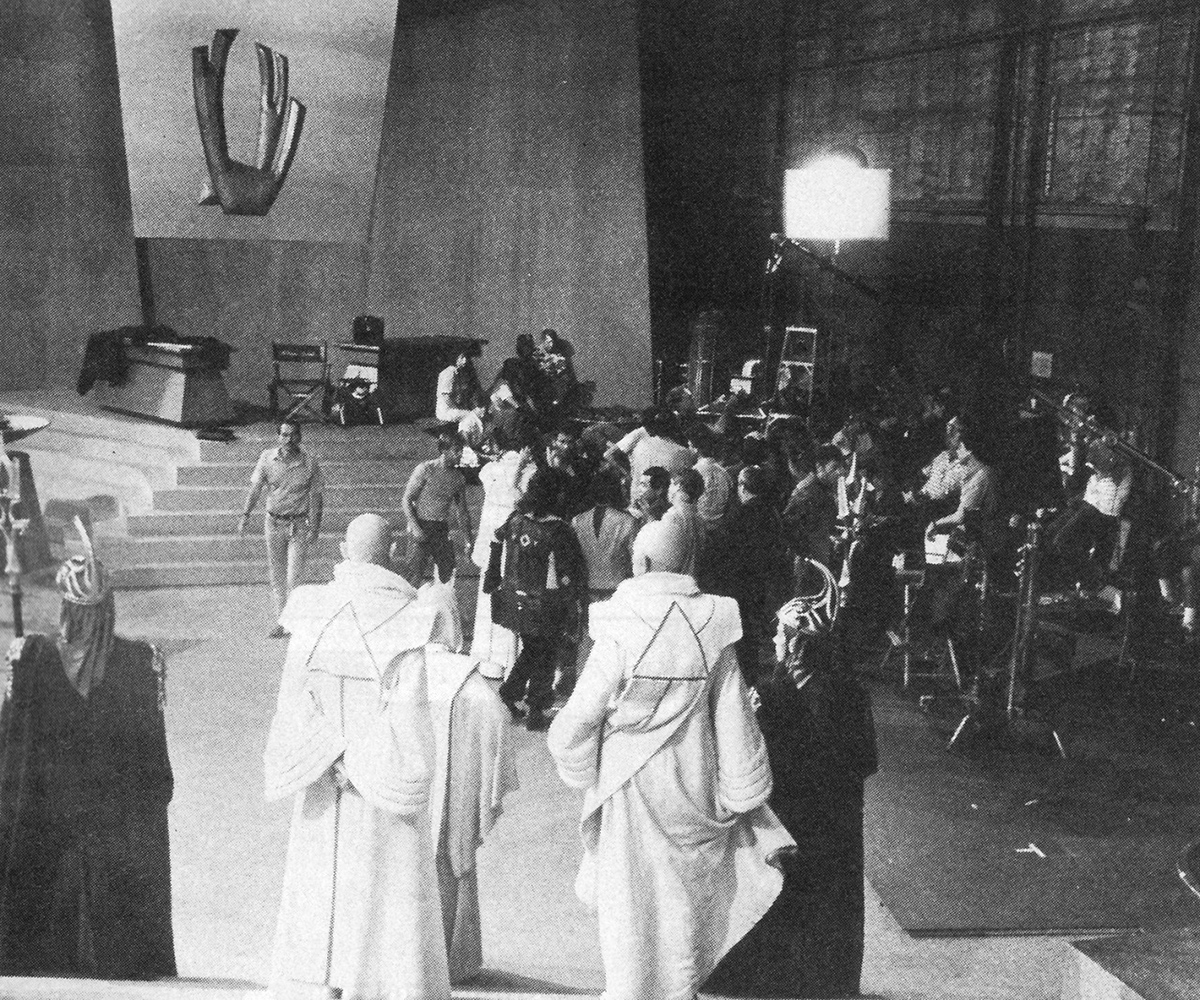

Industrial Light and Magic provided artwork for a scene that was filmed but ultimately cut from the movie in which Spock’s body was carried in a procession up to a Hall of Ancient Thought before being brought out for the ceremony in which his katra was reunited with his body.

George Takei told Starlog in 1986 he was “absolutely aghast” when the scene was cut:

We shot three nights, very expensive, with hundreds of extras on location at Occidental College. After the Bird of Prey lands, the crew comes down the ramp bearing Spock’s body. Then there’s a fleeting glimpse of all the Vulcans. The next scene shows us entering the temple with Dame Judith Anderson. This was a sequence of pageantry, of spectacle, of color, and an opportunity to present this awesome society we call the Vulcan civilization – the religious hierarchy, the aristocrats, the merchant classes, all the gold and silver vestal virgins.

But Visual Effects Art Director Nilo Rodis-Jamero told Star Trek: The Magazine years later that the scene didn’t live up to the concept art:

There was just too much detail, and that took away from the meaning of the scene.

Nimoy and the producers agreed and cut it from the movie.

The Voyage Home

The Voyage Home recycled the Mount Seleya shots from The Search for Spock. The scene in which the Enterprise crew leave Vulcan in their stolen Klingon Bird of Prey was shot on the Paramount parking lot.

Nimoy, who also directed Star Trek IV, recalled in the audio commentary for the 2009 Blu-ray release of the movie that they had searched high and low for a better location but all had shortcomings:

We looked at various canyons, we looked at desert. And there were always problems. Either the look wasn’t right, or it was too far out of town or whatever. And we ended up shooting it on the Paramount lot. And the set construction people and design people did a great job of camouflaging whatever we didn’t want to see. They did it with smoke or a piece of a set, or a flat or some painted canvas or something to hide the background, to hide the buildings that [were] within 30 feet of us.

Tons of reddish dirt and sand were brought in to represent Vulcan’s soil. Writer Howard Weinstein told Star Trek Magazine in 2011 that he half-seriously contemplated scooping up some red dirt in order to sell it as “real Vulcan sand” at a Star Trek convention.

Stock footage from The Voyage Home was used in the Star Trek: Voyager episode “Persistence of Vision,” in which Tuvok hallucinates that he is back on Vulcan.